First, I want to give credit where credit is due so the majority of this post was inspired by the website Property Metrics and their post on IRR. I'm going to take a bit of a different approach and try to explain it a bit more in layman's terms but at the same time give a more technical explanation using the math side of things. Finally, I will use a real world example to better explain it.

IRR

So what is IRR? The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is the yield an investment generates given a series of cash flows over a period of time. More specifically, it is the percentage required to discount future cash flows so that Net Present Value (NPV) of those cash flows equal zero.

Cap rates are sometimes confused with IRR but a few reasons why it's not the same is because cap rates use the net operating income (NOI) generated by the property and omit capital items from the equation. An example would be a tenant improvement allowance paid out to improve a space. Another difference is that you can calculate the IRR both before and after debt to see what impact leveraging has on the investment; NOI never takes into account debt servicing. IRR can be calculated over a monthly, quarterly, yearly or other periodic period; NOI is strictly annual. Finally, NOI only takes into account the current income whereas IRR must have a negative cash flow involved, typically this is the purchase of the asset at Year 0. Why? Let's take a look at the math a bit closer.

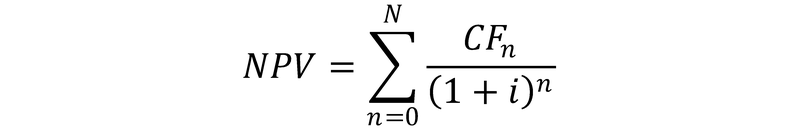

The equation for NPV is as follows:

Where:

N = total number of periods

n = the applicable period (0 <= n <= N)

CF = Cash flow for the nth period

i = required return or discount rate

What the equation means is that you are adding all the cash flows for each period together at a given rate, or:

Since any number with a 0 as the exponent equals 1, the first term is simply the first Cash Flow which is usually the purchase of the asset and is therefore negative (cash goes out). The subsequent numbers are the future cash flows (period 1, 2, ..., up to N) discounted using the rate entered as i. So as n becomes larger (ie further into the future), the denominator becomes bigger and thus that particular cash flow is increasingly reduced compared to a previous period. This is the Time Value of Money concept that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow due to inflation and compounding.

To determine the IRR, you set the NPV (or left hand side of the equation) equal to 0 and solve for i (which is the IRR). There is no easy way to solve for i and Excel and other programs have algorithms to more or less use trial and error until it arrives at a correct value within an acceptable degree of precision. If N is sufficiently large, then calculus can be used as this then becomes an infinite series which converges onto a value provided it meets certain criteria.

So why do we need to have at least one cash flow negative? Because in order for NPV to equal 0, there needs to be an offsetting negative value to the positive ones to arrive at 0. Or put another way, you can't equal zero by adding only positive numbers.

At this point, it is important to note that NPV and IRR are discounting functions which means you are taking future cash flows and discounting them at a required rate of return to determine if the investment meets your targets. This means you are not reinvesting those future cash flows at those rates but merely working back to see if the proposed investment meets your targets today. The formulas assume that you are receiving those future cash flows at the rate of return you require, not that you are investing those future cash flows at those returns.

Real World Example

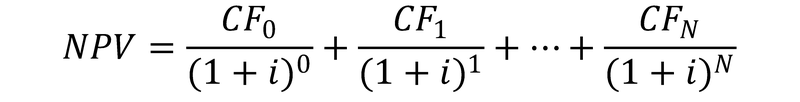

Say you are purchasing an asset for $5,000,000 that generates a 9% cap rate or $450,000 of NOI. This asset has all brand new 10 year absolute net leases in place and after year 5, the NOI increases by 20% to $540,000. However, one of the tenants negotiated a tenant improvement allowance at the start of year 5 to freshen their space up which equals $110,000. To keep the property in top condition, 1% of NOI is allocated every year to be spent on structural reserve. Finally, at the end of the 10 year period, the hope is to sell the asset at an 8% cap rate or $6,750,000. Therefore:

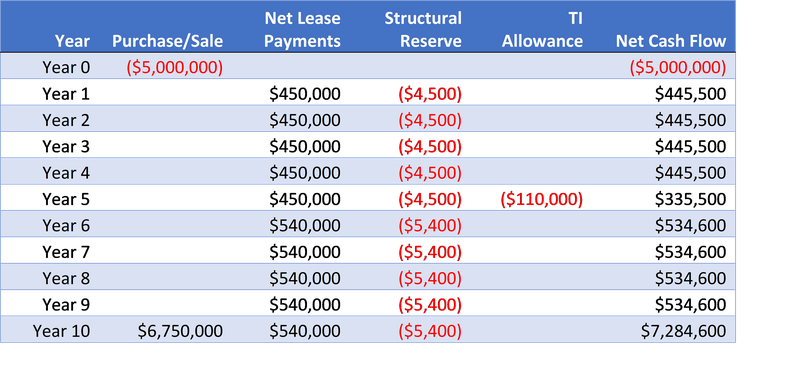

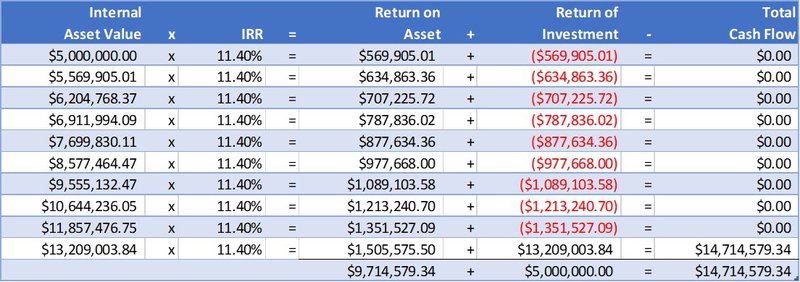

Plugging these numbers into a IRR calculator will result in an IRR of 11.40% (rounded). So what does the 11.40% mean? It means, that given those cashflows occurring at those points of time will result in you earning a 11.40% return on your investment. Here is what is happening with the asset:

The initial $5,000,000 that was invested makes 11.40% on the first year or $569,905.01, of which $445,500 is returned as a cash flow so the remaining $124,405.01 remains with the asset. The same thing happens for each subsequent year until year 10, at which point the asset is sold (or valued at) and the entire value is returned. These numbers only work if the future values are realized, and more importantly, the sale of the asset at $6.750,000 which is what makes IRR a discounting function rather than a rate of return. The total cash flow of $11,540,500 is the initial investment of $5,000,000 plus the return over the holding period of $6,540,500.

Conclusion

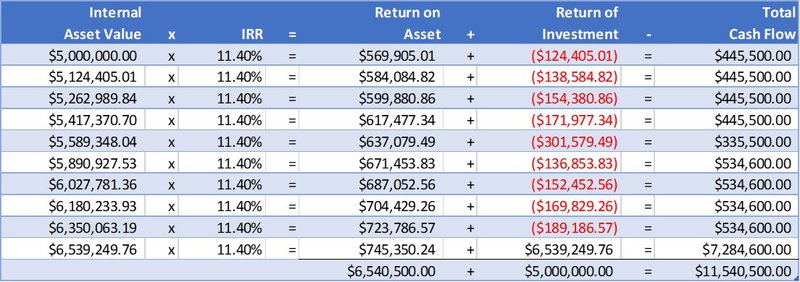

The primary purpose of the IRR is to compare the rates earned for different investments. You can have investments take the same initial investment, earn the same IRR but return different cash flows. For example, taking the $5,000,000 price tag above, investing it for the same holding period at the same IRR but only receiving a payout at the end of the holding period with no interim cashflows results in the following:

So the first scenario, a real estate deal, earns a 11.40% IRR and the second scenario, some other investment, earns the same IRR but returns a larger total cashflow. The reason comes down to the time value of money and the fact that the real estate deal returned part of the investment as interim cashflows over the holding period whereas the other investment returned everything at the end.

Or put another way: if you give me $5M and in 10 years I'll give you back $14.714M, or, give me $5M and in 10 years I'll give you $7.284M but also around $500K each year. What would you choose? In this case it's the same, you earn 11.40% over the 10 years you hold either asset. The IRR allows you to compare when those cashflows occur and whether one is more attractive over the other.